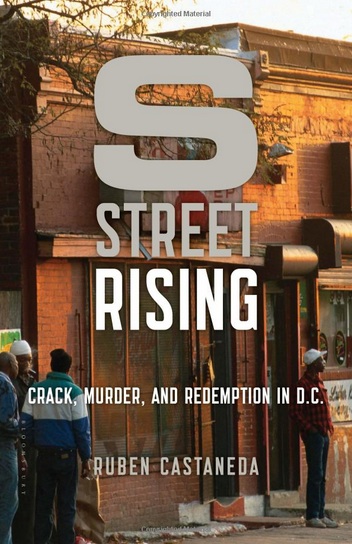

S Street Rising: Crack, Murder -- and Redemption in Rose Park

Dirty, salty snow in rock-hard piles was frozen to the ground at the Rose Park tennis courts near 26th and O Streets in Georgetown on a frigid morning in January in 1998. As most people slept, an unlikely pair were engaged in a life-or-death struggle.

There had been drug-dealing in the park. Tricks turned. It was the 1990s, the decade of crack, Marion Barry’s “bitch set me up,” and corruption in the D.C. police department.

One of the men wore a ski mask. One wore shorts. Neither planned to lose.

Was it a battle over drugs, money? Were they high?

The sounds in the park were not shouts or gunshots, but the thwacks and groans of tennis players in a fight-to-the-death grudge match. Over, well…winning. That game.

“For six years we used to play three times a week – hundreds of times,” said Erik Wemple, previously editor of City Paper, now a media reporter at The Washington Post. “We must have played 450 times.”

“His backhand was an absolute killer,” said John Winslow, former chair of the Art Department at Catholic University and a serious player. “He would always beat me, but I would get up at all hours and play when he wanted to play – at six or seven in the morning. He liked that.”

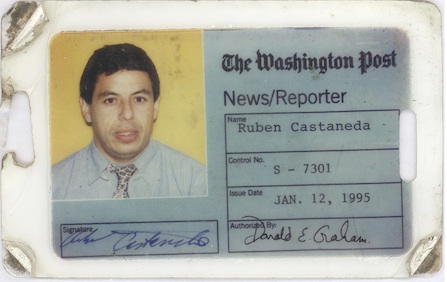

“He” was Ruben Castaneda, metro reporter at The Washington Post. Castaneda was obsessive about tennis. Just as he had been obsessive about reporting on the crack epidemic in Washington, D.C. at the Post. And just as he had been obsessive, for a time in his life, about smoking crack himself.

From S St. Rising, Castaneda’s new book:

I should have gotten out of the car already. I should have been working the crowd, scribbling notes on the mayhem while looking for someone to interview.

But I couldn’t bring myself to get out of my beat-up Ford Escort, pulled up to the curb near the intersection of 5th and O Streets Northwest.

It was the afternoon of December 20, 1990. I was a twenty-nine-year-old night police reporter for the Washington Post. I’d joined the

paper fifteen months earlier and was anxious to make my mark, willing to do whatever the bosses asked. I routinely raced to combat zones to cover drug-crew shootings, even if the trips didn’t yield many bylined stories. Single or even double gangster killings were usually relegated to the briefs column. But this assignment was different: five kids shot in a drive-by as they were walking home from school just before Christmas. Other Post reporters were at the scene, and chances were good that one of us was going to get our name on the front page.

But Castaneda was frozen in his car, afraid that his own crack addiction would be discovered if he got out.

The shooting had taken place just four blocks from S Street Northwest, where once, sometimes twice a week I drove my girl Champagne to make crack buys. Champagne was a “strawberry” – a streetwalker who traded sex for drugs.

The book goes on, in Castaneda’s first-person telling, to chronicle a city in crisis, as seen through a reporter in the grip of his own relentless spiral of crack and alcohol compulsions.

Here is how Tanya Paperny of City Paper describes the book:S Street Rising…replays some of the lowest points in D.C.’s recent history: a time in the 1990s when cops couldn’t seem to do anything about gun violence, when drug-related turf wars led to scores of innocent victims and intimidation killings of witnesses, when my neighborhood of Edgewood was known as “Little Beirut,” and when some children in particularly stricken neighborhoods avoided gunfire by sleeping on mattresses on the floor….

But the main reason you’ll probably hear about S Street Rising is that it’s a memoir from a man who reported on crime at the height of the crack epidemic while he was addicted to crack. While that’s true, Castaneda’s book follows multiple narratives: his own career trajectory, his life as an addict, the spectacular fall of Marion Barry, the professional dramas of then-homicide chief Lou Hennessy, and the coming-of-age story of a small community church located on a lawless S Street NW block.

A few years after Castaneda took his last hit of crack, he sent a note to Stephanie Mencimer, then an investigative reporter at City Paper, complimenting her on a story she had written about problems in the police department. “It was about all these cops who had beaten up their wives and girlfriends and never been prosecuted. It was 1996,” she says.

That winter, Mencimer went to a party with her friend and City Paper colleague Wemple, where the latter encountered Castaneda for the first time. “I overheard Erik talking about his athletic and tennis prowess – I think he had had a couple drinks,” Castaneda says. “So I basically challenged him.”

Castaneda needed to play. Before work, after work – at all hours. He found a loyal nemesis in the taller, younger Wemple.

With razor-sharp crosscourt backhands, a slightly odd serve and the occasional petal-soft drop shot, Castaneda could best almost anyone at the courts, and in the city. But winning wasn’t guaranteed for either man in this case.

Wemple learned the game on manicured courts in upstate New York playing against his two brothers. It was competitive. “You don’t hit, you want to beat the piss out of them. You want to run the pulp out of each other,” he said.

Castaneda taught himself to play on the courts at working-class Mountain View High School in El Monte, California, a majority Latino suburb east of Los Angeles. “At that school, if you showed up and kept coming, you made the team.”

Years later, Wemple and Castaneda started playing in what would become an intense, six-year rivalry – with no regular victor – except the competition itself.

“He had a mortal backhand, really flat, not much spin. The ball wouldn’t bounce very high – it just died,” says Wemple. “And Ruben never gave up on points. He would get everything back.”

There was not a lot of socializing, even in toney Georgetown, where C. Boyden Gray might walk by, Dominique Strauss-Kahn could peep at the courts though his back fence, and Andy Kohut, Founding Director of the Pew Research Center, was a regular.

And Castaneda didn’t stop at the physical game to overcome Wemple. “I would tell him his dark sneakers were going to make his feet sweat,” Castaneda laughs. “I would say things to psyche him out.”

“Yeah, he tried that,” Wemple says.

Earlier this month, the since married Wemple and Mencimer, a Senior Reporter for Mother Jones, hosted a book party for Castaneda in their Logan Circle home.

Post colleagues including Bill Turque, David Montgomery, and Mike DeBonis came to show their support, as did Jim Dickerson of New Community Church, Lou Hennessy (the former D.C. police homicide captain), and D.C. Council candidate Elissa Silverman, who also previously worked at the Post and City Paper.

“I always root for Ruben,” Mencimer said. “He’s been struggling to get this book out for a long time.”

“It was really hard to get this done,” Castaneda says. “I always believed it was a good story, but it took years.”

Just as he wouldn’t be bested by Wemple and others over the years at Rose Park, so too did Castaneda fight for the dream of getting his story published.

The reviews have been good.

So might there be a movie in the offing? The D.C. area has produced several major Hollywood talents who could take an interest. David Nevins, President of Showtime Networks, produced Homeland and Ray Donovan, and worked on Dick Wolf’s Law & Order early in his career. David Dobkin, another graduate of Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda, produced Wedding Crashers and Shanghai Knights. And there's Spike Jonze (né Adam Spiegel, also from Whitman), of Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Her fame.

Who knows whether these D.C. natives might find in Castaneda’s story a good treatment for a movie or TV series.

The author has his Hollywood-speak down: “It’s The Wire meets Crash with a Dash of L.A. Confidential,” he says. “Those are great works of fiction. Everything in S Street Rising is true.”

While he’s suffering from a bad disc in his back, Castaneda keeps busy when he’s not working, playing pick-up basketball now and then. Occasionally, he pulls out a racket to try out his strokes. Maybe someday they'll return.

"That’s really the theme of the book,” he says. “Don’t give up.”

S Street Rising is available at Amazon.com. Read more about the book here.