Simon on Jacobsen Architecture

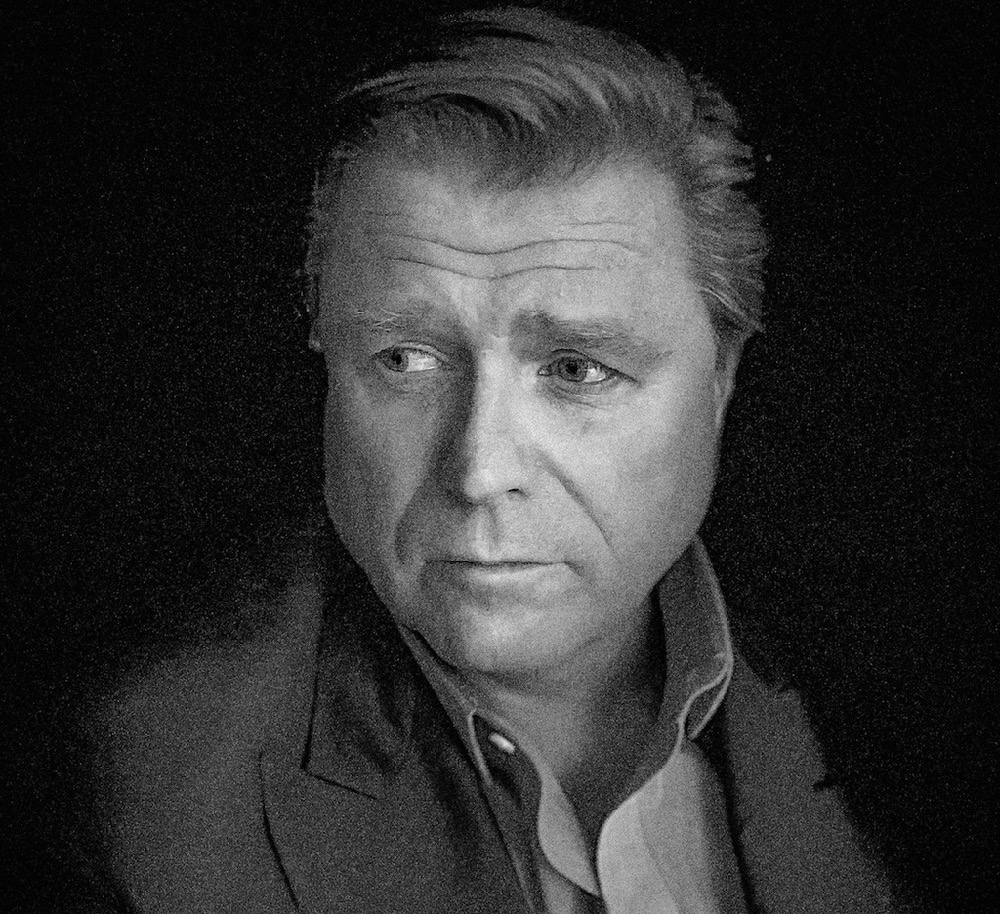

Earlier this week, I had a chance to sit down with founding partner of Jacobsen Architecture, Simon Jacobsen in his Georgetown home. Along with his father, Hugh Newell Jacobsen, this internationally acclaimed firm is best known for its custom residential, commercial and institutional architecture, interiors, furniture and lighting design. And Simon has been a longtime contributor to The Georgetown Dish.

TGD: Can you give our readers a sneak peek at some of the projects included in your fourth book, coming out later this year?

SJ: The new book with the wildly exciting title, Jacobsen Architecture, The work of Hugh Newell Jacobsen and Simon Jacobsen, 2007-2018 will encompass the projects from our partnership together in that period. We had dizzying variations of projects in that time from very little things, to very large things. But the ‘duo-graph’ is going to cover the unique changes and developments when Hugh Jacobsen, one of America's most sought after architects, abruptly disbanded his practice to start a new one with his handsome, charming son, Me. There will be commentary about how we navigated design challenges while working in very far-off and difficult climates, how are two personalities managed the give and take required in a partnership, especially father and son. Hugh often says “My library is filled with the tragedies of fathers and sons working together, but you will not find this one there.” Impossible design regulations and code requirement in Nantucket to laws of physics problems in Rockport, Maine (Stein2) are just a few of the many difficulties any architecture firm will face.

TGD: What is your impression of how this city has changed in the last 25+ years? Your respect for and nostalgia about historic buildings being torn down is well known. Anything in particular you'd like to comment on?

SJ: Washington from it’s beginning is a city of constant ebb tide of change. One of the periods that saw the greatest length of cultural and change was after World War I and again after II when after fighting years of foreign wars and living in European inspired buildings, the city and our country as a whole had had enough. The Washington and their leaders started the long process to disassemble the icons of monarchy based influences of architecture. We saw first-hand what happened at the end of WWII and the citizens, starting a new life ofter all of the hardship and tragedies that war brought to everyone, moved to the suburbs and invented the strip malls and big box grocery chains. This killed many American cities across the country, but Washington was the most profound in my opinion.

TGD: What have been some of your greatest building challenges around the world in terms of historic preservation, dealing with local building laws, geography, climate, etc.?

SJ: The book is going to look closely at our preservation of several important buildings, but the greatest test was Bray House in Maine. Built in 1662 when coastal Maine was considered Massachusetts Bay and the territory of New York, a single two story building was erected by John Bray, a loyalist to Charles II. This little nondescript dwelling of 1,800 square feet would be added onto over the next 300 years and would be swallowed up by additions and adjoining buildings to the point where one could not distinguish the original house. In fact, many of the townsfolk were under that impression and even went as far to assume the 1955 additions were from the time Charles The Second. In 2015, the structure was in serious decay and alarmingly had no historic protections to prevent anyone from taking it down or turning in a Hobby Lobby. We were hired by two celebrity chefs who consulted with me prior to buying it. Although they are patient and highly decent people, I realized while I was standing in the cool Maine maritime breeze, that I had about 45 seconds to come up with a scheme to not only save the building, but also add another 10,000 square feet to it and not repeat it’s history of one bad idea after another. The design that we see today is that same conversation where one has to sing for his dinner.

Looking back I recall being sure they were not going to hire me and that I had ‘laid an egg’, as Hugh would often say about not giving the best pitch to a client. A week later I got the call and I turned to a colleague and said “Oh no, now we have to build this thing.”

Because history is so important to know in architecture, there is an interesting detail to the modern chimneys on the new buildings we designed; they have the distinctive painted black chimney tops on them. This goes back to the American Revolution and the War of 1812 when American loyalists to the King would signify to other loyalists and to the British Navy anchored just 200 feet away, that they identified themselves as subjects of The Crown.

TGD: In terms of what your clients are now looking for in a Jacobsen house/project, has that changed over the years as your international reputation has grown?

*/

SJ: Hugh likes to say, “There is only one firm in the world that does what we do…” and he is right. Because of that, we do not appeal to everyone. But the clients that do commission us for our distinctive work are people who already know our design ethic. Rarely to we have an interview with a person who says “So, what do you do?” or “I am really looking to build something in the style of High Mongolian Renaissance.”

*/

*/